Install (or upgrade) invocation_tree using pip:

pip install --upgrade invocation_tree

Additionally Graphviz needs to be installed.

Run a live demo in the 👉 Invocation Tree Web Debugger 👈 now, no installation required!

Run a live demo in the 👉 Invocation Tree Web Debugger 👈 now, no installation required!

- shows the invocation tree (call tree) of a program in real time

- helps to understand recursion and its depth-first nature

The new @ivt.show decorator interface now allows for scaling to larger code bases.

Bas Terwijn

Inspired by rcviz.

Repetition can be implemented with iteration and recursion. As an example we compute the factorial of 4.

import math

print(math.factorial(4))24

The result is computed with repeated multiplication: 1 * 2 * 3 * 4 = 24.

To implement our own factorial function we can use iteration, a for-loop or while-loop, like so:

def factorial(n):

result = 1

for i in range(1, n+1):

result *= i

return result

print(factorial(4))24

Or we can use recursion, a function that calls itself. Then we also need a base case as stop condition to prevent the function from calling itself indefinitely, like so:

def factorial(n):

if n <= 1: # stop condition

return 1

return n * factorial(n - 1) # function calling itself

print(factorial(4))24

This logic is evaluate as:

factorial(4) = 4 * factorial(3)

= 4 * 3 * factorial(2)

= 4 * 3 * 2 * factorial(1)

= 4 * 3 * 2 * 1

= 4 * 3 * 2

= 4 * 6

= 24

To better understand what is going on when we run the program, we can use invocation_tree:

import invocation_tree as ivt

def factorial(n):

if n <= 1:

return 1

return n * factorial(n - 1)

tree = ivt.blocking() # block and wait for <Enter> key press

tree(factorial, 4) # call function 'factorial' with argument '4'to graph the function invocations where function calls happen on the way down, and where results combine on the way up when a function returns. Run this program and press <Enter> to step through program execution.

Or see it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger.

Each node in the invocation tree represents a function call, and the node's color indicates its state:

- White: The function is currently being executed.

- Green: The function is paused and will resume execution later.

- Red: The function has completed execution and has returned.

For every function call, the package displays its local variables and return value. Changes to the values of these variables over time are highlighted using bold text and gray shading to make them easier to track.

We can also visualize the execution of this program in the Memory Graph Web Debugger:

where the call stack is explicit. Each function call adds a stack frame to the call stack with a reference to its local variables and when a function returns it's stack frame is removed from the call stack. But when later a function calls itself multiple times the invocation_tree will give us a better visualization than memory_graph, so we will use that here mostly.

With recursion we often use a divide and conquer strategy, splitting the problem in subproblems that are easier to solve. With factorial we split factorial(4) in a 4 and factorial(3) subproblem.

Use recursions to compute the sum of all the values in a list (hint: split for example the list [1, 2, 3, ...] in head 1 and tail [2, 3, ...]).

def sum_list(values):

# <your recursive implementation>

print(sum_list([3, 7, 4, 9, 2])) # 25Rewrite this iterative implementation of decimal to binary conversion to a recursive implementation.

def binary(decimal):

bin = []

while decimal > 0:

decimal, remainder = divmod(decimal, 2)

bin = [remainder] + bin

return bin

print( binary(22) ) # [1, 0, 1, 1, 0]Checking that [1, 0, 1, 1, 0] is the correct binary representation for decimal 22:

| 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| bits | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| contrib | +16 | 0 | +4 | +2 | 0 | =22 |

In some functional and logical programming languages (e.g. Haskell, Prolog) there are no loops so there only is recursion to implement repetition, but in Python we have a choice between recursion and iteration. Generally iteration is chosen in Python as it is often faster and many find it easier to understand. However, in some situations recursion comes with great benefits so it's important to master both ways.

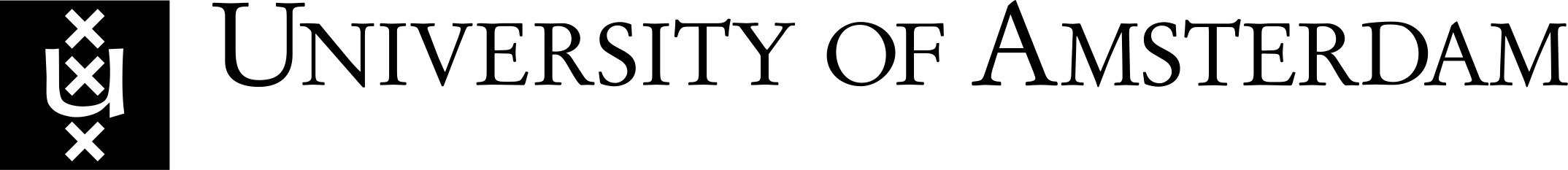

We can use recursion to compute all permutation of a number of elements with replacement (each element can be used any number of times). All permutations of length 3 of elements 'L' and 'R' can be made by moving down a tree for 3 steps and going Left and Right at each step:

This can be implemented recursively, using a divide and conquer strategy, with a function calling itself multiple times, like:

import invocation_tree as ivt

def permutations(elements, perm, n):

if n == 0: # stop condition, check if all steps are used up

print(perm)

else:

for element in elements: # for each element

permutations(elements, perm + element, n-1) # add it and do next step

tree = ivt.blocking()

tree(permutations, 'LR', '', 3) # all permutations of L and R of length 3LLL

LLR

LRL

LRR

RLL

RLR

RRL

RRR

Or see it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

Or see it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

The visualization shows the depth-first nature of recursion. In each step the first elements is chosen first, and quickly the bottom of the tree is reached. Then the permutation is printed, the function returns, one step back is made, and the next element is chosen. When each element had it's turn the function returns and another step back is made. This pattern repeats until all permutations are printed.

We can also iterate over all permutations with replacement using the product() function of iterools to get the same result:

import itertools as it

for perm in it.product('LR', repeat = 3):

print(perm)The benefit recursion brings is that it gives us more control over which permutations are generated. For example, if we don't want neighboring elements to be equal in all permutatations of 'A', 'B' and 'C' then we could simply write:

import invocation_tree as ivt

def permutations(elems, perm, n):

if n == 0:

print(perm)

else:

for element in elems:

if len(perm) == 0 or not perm[-1] == element: # test neighbor

permutations(elems, perm + element, n-1)

tree = ivt.blocking()

tree(permutations, 'ABC', '', 3) # all permutations of A, B, C of length 3 without equal neigborsThis generates all permutation but without equal neighors like AAB:

ABA

ABC

ACA

ACB

BAB

BAC

BCA

BCB

CAB

CAC

CBA

CBC

Or see it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

Or see it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

With recursion we can stop neighbors from being equal early, in contrast to iteration, where we would have had to filter out a permutation with equal neighbors after it was fully generated, which could be much slower and would require a more complex program.

Write function palindromes(elems, perm, n) that print all permutations with replacements of elements in elems of length n that are palindrome ('ABABA' is palindrome because if you read it backwards it's the same). The function call palindromes('ABC', '', 3) should result in these lines in any order:

AAA

ABA

ACA

BAB

BBB

BCB

CAC

CBC

CCC

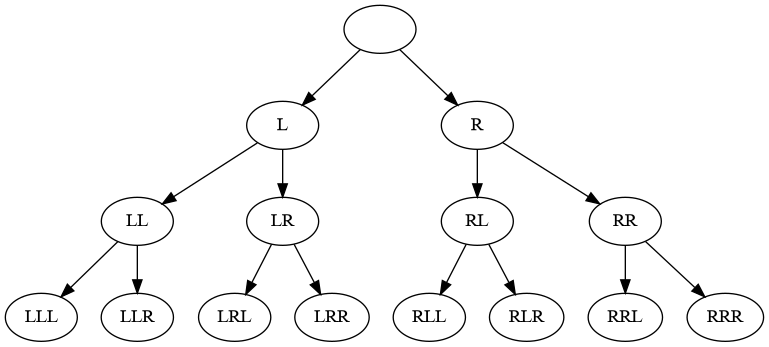

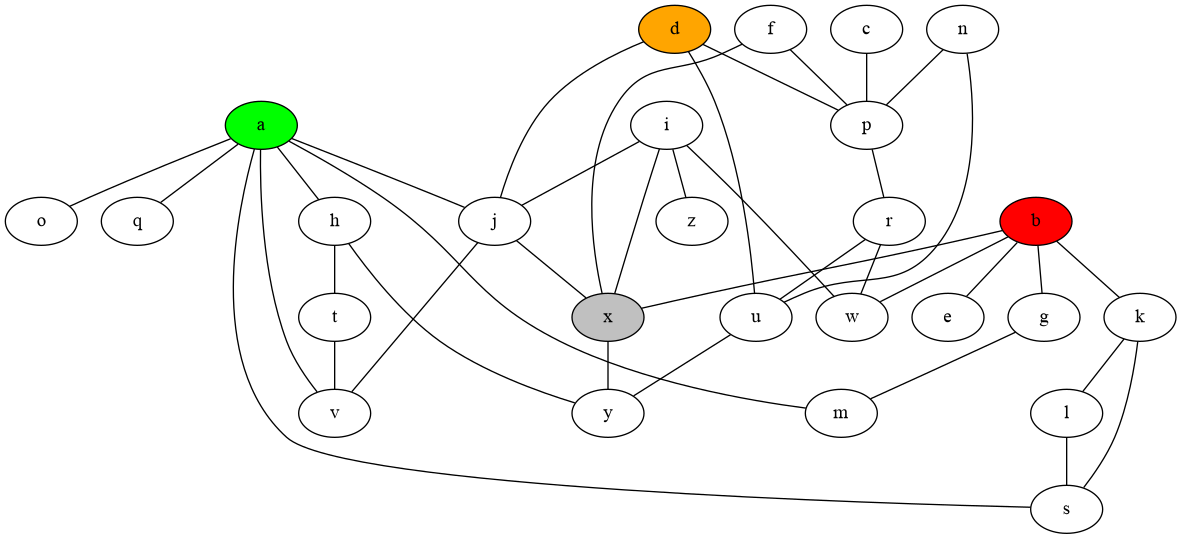

A graph is defined by nodes, which we name with letters, and edges that define the connections between nodes. For example edge ('a', 'j') defines that there is a connection between node a and node j. In a bidirectional graph a connection betweeen two nodes can be used in both directions, from a to j and from j to a.

We define a bidirectional graph by a list of edges:

edges = [('a', 'j'), ('f', 'j'), ('c', 'e'), ('b', 'd'), ('b', 'e'), ('f', 'g'),

('g', 'i'), ('h', 'i'), ('e', 'h'), ('a', 'i'), ('b', 'h'), ('b', 'f')]

that can be visualized as:

To print all the paths from a to b without going over the same node twice, we can use this recursive implementation:

edges = [('a', 'j'), ('f', 'j'), ('c', 'e'), ('b', 'd'), ('b', 'e'), ('f', 'g'),

('g', 'i'), ('h', 'i'), ('e', 'h'), ('a', 'i'), ('b', 'h'), ('b', 'f')]

def edges_to_connections(edges: list[tuple[str, str]]) -> dict[str,list[str]]:

""" Returns a dict with for each node the nodes it is connected with. """

connections = {}

for n1, n2 in edges:

if not n1 in connections:

connections[n1] = []

connections[n1].append(n2)

if not n2 in connections:

connections[n2] = []

connections[n2].append(n1)

return connections

def print_all_paths(connections, path, goal):

current = path[-1] # last node in path is the current node

if current == goal:

print(path)

else:

valid_connections = connections[current] # get nodes connected to current

for n in valid_connections:

if n not in path: # don't use same node twice

print_all_paths(connections, path + n, goal)

connections = edges_to_connections(edges)

print_all_paths(connections, 'a', 'b')ajfgiheb

ajfgihb

ajfb

aigfbaihb

aiheb

aihb

See it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

This would be much harder to implement with iteration and shows the power of recursion.

Adding temporarely debug print statements is in general a good technique to understand code, and is particularly helpful with recursion. Here we added a debug print statement when adding and removing a node from the path. As a result we can now in the output see how all paths are build step by step:

See it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

Add temporary debug prints wherever behavior isn’t clear. Experiment with what and how you print to maximize clarity.

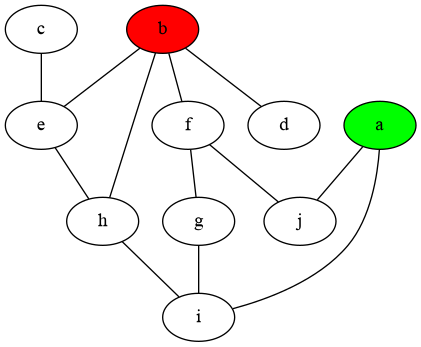

In this larger bidirectional graph, print all the paths of length 7 that connect node a to node b where going over the same node multiple times is allowed (avjxbxb is one such path, there are 114 such paths in total).

edges = [('a', 's'), ('i', 'z'), ('c', 'p'), ('d', 'p'), ('d', 'u'), ('b', 'e'), ('b', 'g'),

('f', 'p'), ('g', 'm'), ('h', 't'), ('h', 'y'), ('i', 'w'), ('i', 'j'), ('i', 'x'),

('k', 's'), ('k', 'l'), ('a', 'm'), ('n', 'u'), ('a', 'o'), ('a', 'v'), ('n', 'p'),

('a', 'q'), ('a', 'h'), ('p', 'r'), ('l', 's'), ('t', 'v'), ('u', 'y'), ('j', 'v'),

('a', 'j'), ('r', 'w'), ('r', 'u'), ('f', 'x'), ('x', 'y'), ('j', 'x'), ('d', 'j'),

('b', 'k'), ('b', 'x'), ('b', 'w')]If instead of printing we want to collect each result in a list for later use, we can use the return value of our recursive function, like in this example for our earlier permutation problem.

import invocation_tree as ivt

def permutations(elements, perm, n):

if n == 0:

return [perm]

else:

results = []

for element in elements:

results += permutations(elements, perm + element, n-1)

return results

tree = ivt.blocking()

print(tree(permutations, 'LR', '', 3))['LLL', 'LLR', 'LRL', 'LRR', 'RLL', 'RLR', 'RRL', 'RRR']

See it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

However, sometimes it is easier to pass a list (or any other mutable container type) as an extra argument in the recursion to collect the results in. This is also faster because now just one list is used instead of each function call having to create its own results list.

import invocation_tree as ivt

def permutations(elements, perm, n, results):

if n == 0:

results.append(perm)

else:

for element in elements:

permutations(elements, perm + element, n-1, results)

tree = ivt.blocking()

results = []

tree(permutations, 'LR', '', 3, results)

print(results)['LLL', 'LLR', 'LRL', 'LRR', 'RLL', 'RLR', 'RRL', 'RRR']

See it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

Create a list with all paths of length 10 in the larger bidirectional graph that go from a to b, and that do go via d but do not go via x (amajdjaskb is one such path, there are 145 such paths in total).

Where is the best place in the code to test for x to make the program run fast?

edges = [('a', 's'), ('i', 'z'), ('c', 'p'), ('d', 'p'), ('d', 'u'), ('b', 'e'), ('b', 'g'),

('f', 'p'), ('g', 'm'), ('h', 't'), ('h', 'y'), ('i', 'w'), ('i', 'j'), ('i', 'x'),

('k', 's'), ('k', 'l'), ('a', 'm'), ('n', 'u'), ('a', 'o'), ('a', 'v'), ('n', 'p'),

('a', 'q'), ('a', 'h'), ('p', 'r'), ('l', 's'), ('t', 'v'), ('u', 'y'), ('j', 'v'),

('a', 'j'), ('r', 'w'), ('r', 'u'), ('f', 'x'), ('x', 'y'), ('j', 'x'), ('d', 'j'),

('b', 'k'), ('b', 'x'), ('b', 'w')]In the permutation problem we could choose to use mutable type list to represent a permutation instead of the immutable type str we used before. This can be done in two ways. One way is to use the + list concatenation operator to add elements to the permutation, but this is slow because this creates a whole new list each time:

def permutations(elements, perm, n):

if n == 0:

print(perm)

else:

for element in elements:

permutations(elements, perm + [element], n-1) # creates new list, SLOW!

permutations('LR', [], 3)The Memory Graph Web Debugger shows that each recursive function call has it's own list copy.

The Invocation Tree Web Debugger shows that all permutation are generated in the same way as when we used immutable type str to represent each permutation.

A second way is to mutate the list value with the += operator or append() function and then after the recursive call to undo this action to restore its original value. This way we avoid creating new lists so this is much faster. We now use the same list in each recursive function call. We couldn't do this before with immutable type str because a value of immutable type is always automatically copied when we change it. However, now we have to take care to correctly undo each action we take so the code can get it a bit more complex, but this generally is worth it for faster execution. This style of recursion is often called backtracking with in-place mutation.

def permutations(elements, perm, n):

if n == 0:

print(perm)

else:

for element in elements:

perm.append(element) # do action that mutates, FAST!

permutations(elements, perm, n-1)

perm.pop() # undo action

permutations('LR', [], 3)The Memory Graph Web Debugger now shows that all function calls use the same list.

The Invocation Tree Web Debugger shows that all permutation are generated but with each action being undone so that in the end the list is empty again.

Rewrite your code of exercise5 so that it uses a list to represent each path and uses backtracking with in-place mutation so that a single list is used in each recursive function call for faster execution. For example the path 'amajdjaskb' should now be represented as ['a', 'm', 'a', 'j', 'd', 'j', 'a', 's', 'k', 'b'].

We can combine recursion and lazy evaluation using the yield and yield from keywords. We use yield to produce a value, and we use yield from when calling each function that (indirectly) produces a value using yield. Here we see an example with the permutations() function:

def permutations(elements, perm, n):

if n == 0:

yield perm

else:

for element in elements:

yield from permutations(elements, perm + element, n-1)

generator_function = permutations('LR', '', 3)

for perm in generator_function:

print(perm)The first call to the permutations() function now results in a generator_function where we can iterate over to get all permutations that are yielded.

The Invocation Tree Web Debugger gives an idea about how lazy evaluation is implemented. When we read a value from the generator_function the permutations() functions get called recursively until a permutation is yielded and then all permutations() calls return. When we read the next value the previous state of the recursion is restored and execution continues until the next permutation is yielded. This patterns repeats until all the recursive calls are completed and the generator is used up. Unfortunately this process makes the tree difficult to read, something we might improve in the future. At least it now gives an idea about the overhead of the lazy evaluation of recursive functions, the price we pay for not having to use memory for the results list.

Rewrite your code of exercise6 so that get_all_paths() recursion is evaluated lazily.

Another nice example of divide-and-conquer is the recursive quicksort algorithm. It works by choosing a pivot element and splitting the list into elements smaller than the pivot, equal to the pivot, and larger than the pivot. The smaller and larger sublists are then quicksorted recursively. When we get to the point a sublist has zero or one element, then it is sorted. When returning, these sorted sublists are then combined with the elements equal to the pivot to produce a larger sorted lists.

import invocation_tree as ivt

def quick_sort(values):

if len(values) <= 1:

return values

pivot = values[0] # choose arbitrarily the first as pivot

smaller = [x for x in values if x < pivot]

equal = [x for x in values if x == pivot]

larger = [x for x in values if x > pivot]

return quick_sort(smaller) + equal + quick_sort(larger)

values = [7, 4, 10, 11, 2, 6, 9, 1, 5, 3, 8, 12]

print('unsorted values:',values)

tree = ivt.blocking()

values = tree(quick_sort, values)

print(' sorted values:',values)unsorted values: [7, 4, 10, 11, 2, 6, 9, 1, 5, 3, 8, 12]

sorted values: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

See it in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger

Add a key argument so that we can use the quick_sort(values, key=None) function to sort each value x in values as if it was value key(x), in exactly the same way as how the sorted(iterable, key=None) function works. For example:

- The call

quick_sort([1, 3, 4, 2], key = lambda x : -x)should return[4, 3, 2, 1]because then each value is sorted by its negative value [-4, -3, -2, -1]. - The call

quick_sort(['aaa', 'bb', 'c'], key = lambda x : len(x))should return['c', 'bb', 'aaa']because then each value is sorted by its length [1, 2, 3].

Sort the values as normal when key is None.

In the Jugs Puzzle we have a set of jugs of various capacities. Our goal is to get a jug with a certain amount of liquid in it. In each step we can take one of these actions:

- fill one jug until it is full

- empty one jug until it is empty

- pour from jug A to jug B until A is empty or B is full

In the first puzzle instance we have a jug with 3 liter capacity, a jug with 5 liter capacity, and our goal is to get to a jug with 4 liters in it. We already have a breadth-first algorithm that solves this puzzle:

If we run this code we get a solution:

$ python jugs_breadth_first.py 4 3,5

Goal is to get a jug with 4 liters.

We start with jugs: 0/3 0/5

generation0: [0/3 0/5]

0/3 0/5 (0, 3) -> 3/3 0/5

0/3 0/5 (1, 5) -> 0/3 5/5

generation1: [3/3 0/5, 0/3 5/5]

3/3 0/5 (0, 1, 3) -> 0/3 3/5

3/3 0/5 (1, 5) -> 3/3 5/5

0/3 5/5 (1, 0, 3) -> 3/3 2/5

generation2: [0/3 3/5, 3/3 5/5, 3/3 2/5]

0/3 3/5 (0, 3) -> 3/3 3/5

3/3 2/5 (0, -3) -> 0/3 2/5

generation3: [3/3 3/5, 0/3 2/5]

3/3 3/5 (0, 1, 2) -> 1/3 5/5

0/3 2/5 (1, 0, 2) -> 2/3 0/5

generation4: [1/3 5/5, 2/3 0/5]

1/3 5/5 (1, -5) -> 1/3 0/5

2/3 0/5 (1, 5) -> 2/3 5/5

generation5: [1/3 0/5, 2/3 5/5]

1/3 0/5 (0, 1, 1) -> 0/3 1/5

2/3 5/5 (1, 0, 1) -> 3/3 4/5

=== solution:

0/3 0/5 - Fill jug 1 with 5

0/3 5/5 - Pour 3 from jug 1 to jug 0

3/3 2/5 - Empty jug 0 with -3

0/3 2/5 - Pour 2 from jug 1 to jug 0

2/3 0/5 - Fill jug 1 with 5

2/3 5/5 - Pour 1 from jug 1 to jug 0

3/3 4/5 -

Where:

0/3represents a jug with0liter content and3liter capacity.(0, 3)represents the action of taking jug at index0and filling it with3liters(0, 1, 2)represents the action of pouring2liters from jug at index0to jug at index1

The breadth-first algorithm works and gives us the shortest path to a goal state, but to do that it uses a lot of memory to store each generation and all jugs states it has seen. Now we also want an algorithm that uses much less memory.

Write a recursive solver for the Jugs Puzzle that uses less memory by searching for the solution in a depth-first manner.

- A solution may not have the same jugs state multiple times (this also avoids infinite loops).

- It is not necessary to find the shortest path to a goal state (like breadth-first does).

Use the decorator interface to visualize the execution on your system (not the Invocation Tree Web Debugger) because that allows you to easily choose which functions show up in the tree.

solution exercise8: First try it yourself, we give the solution here for comparison.

A harder more fun instance of this puzzle is with jugs with capacity 3, 5, 34 and 107 liter and the goal of getting to a jug with 51 liters.

$ python jugs_breadth_first.py 51 3,5,34,107

The Invocation Tree Web Debugger gives examples of the most important configurations.

It can be useful to hide certian variables to avoid unnecessary complexity. This can be done with:

tree = ivt.blocking()

tree.hide_vars.add('functionname.variablename') # or:

tree.hide_vars.add('namespace.functionname.variablename')Or hide certain function calls:

tree = ivt.blocking()

tree.hide_calls.add('functionname') # or:

tree.hide_calls.add('namespace.functionname')Or ignore certain function calls so that all it's children are hidden too:

tree = ivt.blocking()

tree.ignore_calls.add('namespace.functionname')With the re: prefix we can use regular expresssions, for example:

tree = ivt.blocking()

tree.ignore_calls.add(r're:namespace\..*')ignores all functions starting with namespace..

A better way to hide functions is to use the @ivt.show decorator on only the functions you want to graph but this can only be used when running the code locally and not in the Invocation Tree Web Debugger. The decorator uses the global ivt.decorator_tree tree.

import invocation_tree as ivt

ivt.decorator_tree = ivt.blocking() # set tree used by decorator

#ivt.decorator_tree = ivt.blocking_each_change() # block at each change, much slower

#ivt.decorator_tree = ivt.debugger() # for VS Code or PyCharm debugger

@ivt.show # use this decorator to select which functions to graph

def permutations(elements, perm, n):

if n == 0:

print(perm)

else:

for element in elements:

perm.append(element) # do action that mutates

permutations(elements, perm, n-1)

perm.pop() # undo action

permutations('LR', [], 3) # all permutations of L and R of length 3For convenience we provide these functions to set common configurations:

- ivt.blocking(filename), blocks on function call and return

- ivt.blocking_each_change(filename), blocks on each change of value

- ivt.debugger(filename), non-blocking for use in debugger tool (open <filename> manually)

- ivt.gif(filename), generates many output files on function call and return for gif creation

- ivt.gif_each_change(filename), generates many output files on each change of value for gif creation

- ivt.non_blocking(filename), non-blocking on each function call and return

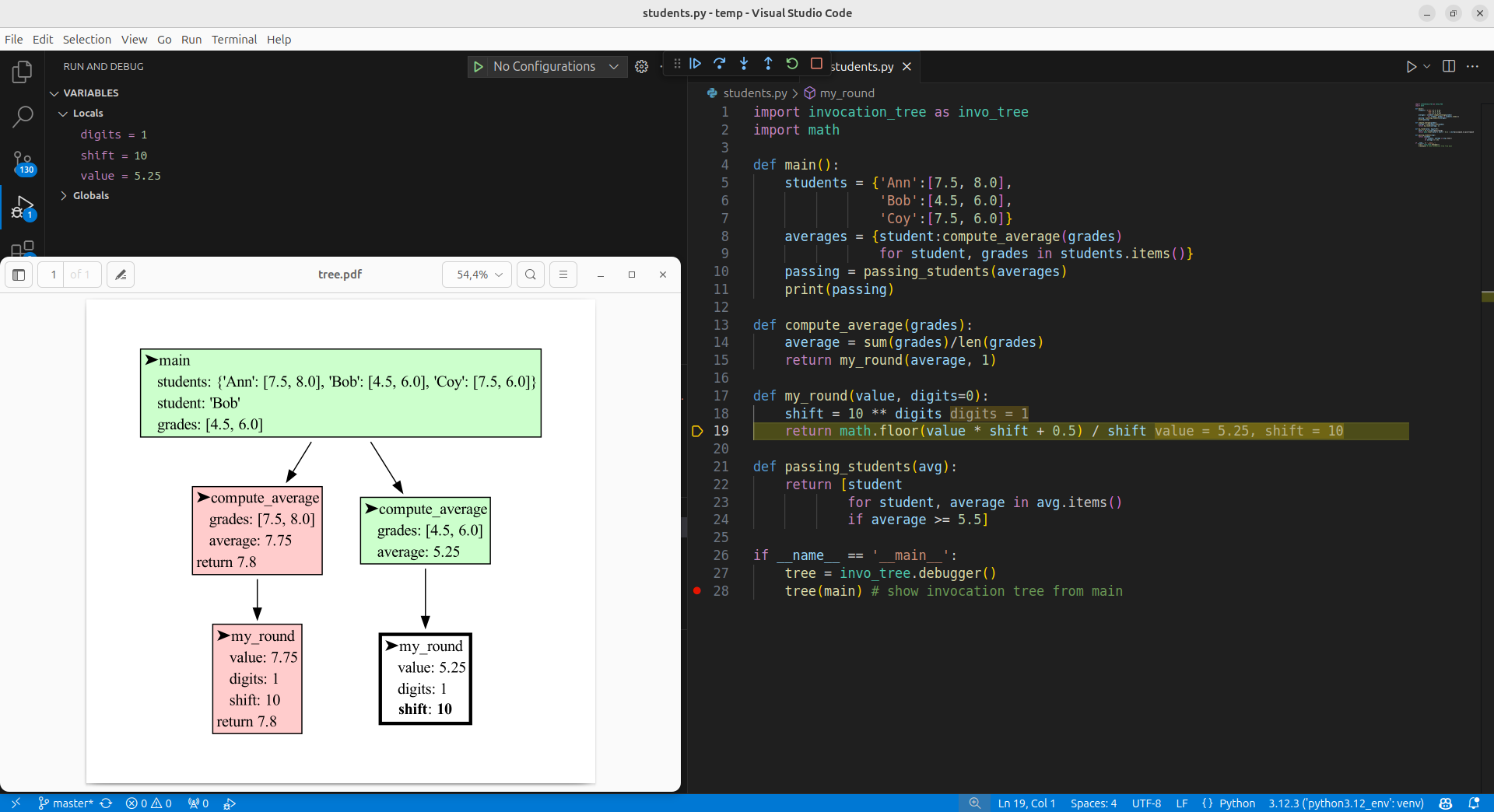

To visualize the invocation tree in a debugger tool, such as the integrated debugger in Visual Studio Code, use:

tree = ivt.debugger()

tree(som_function, arg1, arg2)and open the 'tree.pdf' file in the local directory manually.

More detailed configurations can be set on an Invocation_Tree objects:

tree = ivt.Invocation_Tree()- tree.filename : str

- filename to save the tree to, defaults to 'tree.pdf'

- tree.show : bool

- if

Truethe default application is open to view 'tree.filename'

- if

- tree.block : bool

- if

Trueprogram execution is blocked after the tree is saved

- if

- tree.src_loc : bool

- if

Truethe source location is printed when blocking

- if

- tree.each_line : bool

- if

Trueeach line of the program is stepped through

- if

- tree.max_string_len : int

- the maximum string length, only the end is shown of longer strings

- tree.gifcount : int

- if

>=0the out filename is numbered for animated gif making

- if

- tree.indent : string

- the string used for identing the local variables

- tree.color_active : string

- HTML color for active function

- tree.color_paused* : string

- HTML color for paused functions

- tree.color_returned*: string

- HTML color for returned functions

- tree.to_string : dict[str, fun]

- mapping from type/name/id to a to_string() function for custom printing of values

- tree.hide_vars : set()

- set of all variables names that are not shown in the tree

- tree.hide_calls : set()

- set of all functions names that are not shown in the tree

- tree.ignore_calls : set()

- set of all functions names that are not shown in the tree, including its children

- tree.fontname : str

- the font used in the graph, default 'Times-Roman' (widely available on the web)

- tree.fontsize : str

- the font size used in the graph, default '14'

- Adobe Acrobat Reader doesn't refresh a PDF file when it changes on disk and blocks updates which results in an

Could not open 'tree.pdf' for writing : Permission deniederror. One solution is to install a PDF reader that does refresh (SumatraPDF, Okular, ...) and set it as the default PDF reader. Another solution is torender()the graph to a different output format.

The invocation_tree package visualizes function calls at different moments in time. If instead you want a detailed visualization of your data at the current time, check out the memory_graph package.